History

Read these and more on our social media:

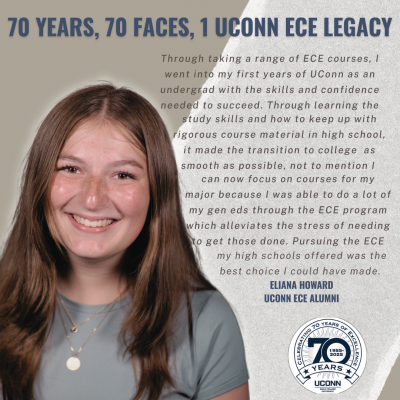

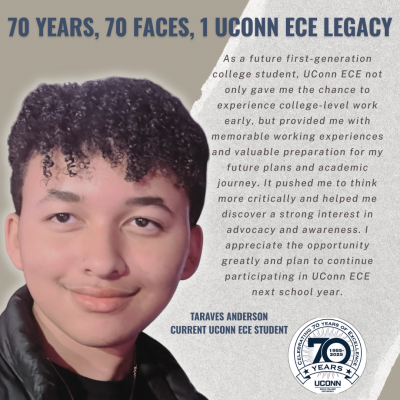

70 Years, 70 Faces, 1 UConn ECE Legacy

In 2025-2025, UConn Early College Experience (née High School Cooperative Program) celebrates 70 years of offering UConn credits to high school students. Now, we want to celebrate you.

Were you part of UConn ECE or the High School Co-op Program as a student, instructor, or administrator? Are you the parent of a UConn or Co-op Alumni? We're collecting stories for a special anniversary campaign - and we'd love to hear yours!

We're especially looking for (but not limited to):

- Multi-generational ECE families

- "Full-circle" journeys (such as former students who became instructors or administrators)

- Instructors/ administrators who can see the impact

- Notable alumni doing amazing things

- First generation college students

- Students who were greatly impacted taking UConn courses in high school

- Parents of current/ former students who see how a college course positively affects their child(ren)

Selected contributors will be featured on UConn ECE social media and in the UConn ECE Magazine as part of our 70 Year, 70 Faces campaign.

Be on of the 70 faces who help us honor this legacy!

The Biggest Branch: UConn ECE Celebrates 60 years (2015)

well as a serious engagement with NACEP. In this period expectations were elevated, professional development was expanded and improved, academic rigor more accurately recorded, and the program invested in research to understand the program as a vital tool for student success [see article of transfer credit database Page 4]. Indeed, we are a national model for concurrent enrollment and are peers with other elite universities like Syracuse University, Indiana University, and the University of Washington. While the program has certainly grown and developed over the last 60 years, the core of the program has stayed the same. UConn ECE is dedicated to deep academic partnerships that provide access to and preparation for higher education at the high schools. We value our relationship with the departments and the high schools, and look forward to continued strength as we work together for student success.

well as a serious engagement with NACEP. In this period expectations were elevated, professional development was expanded and improved, academic rigor more accurately recorded, and the program invested in research to understand the program as a vital tool for student success [see article of transfer credit database Page 4]. Indeed, we are a national model for concurrent enrollment and are peers with other elite universities like Syracuse University, Indiana University, and the University of Washington. While the program has certainly grown and developed over the last 60 years, the core of the program has stayed the same. UConn ECE is dedicated to deep academic partnerships that provide access to and preparation for higher education at the high schools. We value our relationship with the departments and the high schools, and look forward to continued strength as we work together for student success.The Development of Concurrent Enrollment at the University of Connecticut (2019)

By Kathrine Grant, January 2019

Albert E. Waugh served the University of Connecticut from 1924 to 1965 as both an instructor and an administrator. For 15 years, from 1950 to 1965, Waugh worked at the Provost for the University and was responsible for overseeing the administrative and academic functioning of the University (UConn Library). Beyond the service he provided to the University, one of Waugh’s lasting legacies is a meticulously kept journal spanning 1941 to 1974; in it, he details both his personal and professional life. Housed at the University of Connecticut Library’s Archives and Special Collections, the Albert E. Waugh Papers provide a unparalleled amount of insight into the workings of the University and community at large during Waugh’s tenure as a University official.

Beginning in 1941, Waugh detailed the day-to-day concerns that he faced in the various roles he served in. One of his chief and most constant concerns was about the academic integrity of the University, with special consideration to the admittance procedures. The February 13, 1941 meeting of the University Senate and the subsequent acceptance of new standards for admission led Waugh to be concerned about the “continued and thoughtless reductions at [the] institution” and that the University might turn into a “non-intellectual copy of mid-western universities” (Waugh, 2/13/41). Just two years before, the Connecticut State College had become the University of Connecticut (Stave, 2006); with this change came concerns about maintaining the integrity of the roots of the institution as a land-grant and agricultural school (Stave, 2006).

In 1942, with World War II having started three years prior, the University was adapting to the influences of a wartime society (Red Brick). On January 9, 1942, the President of the University, Albert N. Jorgensen, held a heavily attended staff meeting titled “The readjustment of the college to the war situation” (Waugh, 1/9/42). Jorgensen had noted that the there was concern about the effects of the war effort on colleges and that the executive committee of the Land Grant Colleges’ Presidents had passed a number of resolutions that reflected these concerns (Waugh, 1/9/42). Among these resolutions was the change to accelerate the rate of education available to students, “favoring summer sessions, shorter terms, [and the] acceptance of highstanding high school juniors by colleges…” (Waugh, 1/9/42). Early acceptance and enrollment for these students would allow them to get a head-start on their academic careers so that they would be able to join the workforce or armed forces early--critical factors in the overall wartime effort. It was here that the concept of early enrollment began at the University Connecticut.

The following two years saw the University continue to expand and grow as during the wartime effort. Waugh, along with other University officials, continued to worry over the quality of education offered to students at UConn as well as the quality of the educational background that admits brought. In the end of 1944, Waugh notes a conversation he had with President Jorgensen where he focused on an idea he had been “mulling over for some time” (Waugh, 12/11/1044). Waugh wanted to set up:

“A ‘Connecticut Junior Academy of Arts and Letters,’ electing each year a few outstanding high-school scholars who have either done outstanding work on on tests or who have been recommended by their own high-school instructors for work on special projects which they have carried out” (Waugh, 12/11/1944).

President Jorgensen, Waugh notes, had an ideal along similar lines, and a committee was formed to consider the proposition, upon which Waugh served (Waugh, 12/11/1944).

In the following year, Waugh notes a discussion he had with Jorgensen about the creation of a “junior college,” or General College at the University, but both men agreed that the campus was not ready for that (Waugh, 2/5/1945). There was also administrative level conversations surrounding offering high-school level algebra classes at the University--for college credit (Waugh, 10/25/1945). Waugh strongly opposed this idea and was even concerned that the University might, in the first place, be offering high-school level classes (Waugh, 10/25/1945). To Waugh, it was essential the the University maintained integrity in the level of academics and scholarship not only that it offered to students but also that it expected of students.

On January 29, 1946, Waugh, along with other University officials, met with the Connecticut High School Principals Association (this was not an official title, but one that Waugh gave to the group) (Waugh, 1/29/1946). The group had “invited the various colleges of Connecticut to send representatives to discuss what could be done for next June's graduating class, now that the colleges are loaded down with returning veterans” (Waugh, 1/29/1946). The two suggestions were:

- That the colleges set up the freshman year of college work in high schools throughout the state, to be taught by staff selected and paid by the colleges, with the colleges charging regular tuition, and with the credit acceptable at all cooperating colleges.

- That the high schools set up such a program of their own, using their own teachers (who would be approved in advance by the colleges in each individual case) and using outlines supplied by the colleges, and the colleges would in turn promise to honor the credit so obtained.

The idea was well-received by the colleges. Yet, the issue of space provided an immediate concern for the representatives; with veterans now returning to campus, space was at a premium. The University was even struggling to ensure that students at extension campuses (now considered branch campuses) would have space on the Storrs campus after they completed their two years at an extension campus (Waugh, 1/29/1946).

The following several years were quiet regarding the development of the idea of college classes offered to high school students as the University continued to grow, adapt, and evolve. In a 1952 entry, Waugh notes that there was meeting of the Senate’s Committee on Curricula and Courses in which his proposal to admit “a bright few youngsters who have not graduated from high school” was received with significant interest (Waugh, 4/30/1952). Waugh noted additional meetings in June—where the committee continued to be “favorably disposed” (Waugh, 6/10/1952)—and in November, where the committee also heard from a Yale representative on their acceptance of “‘pre-induction scholars’” (Waugh, 11/18/1952). The committee met again in December and devoted much of their time to considering this proposal (Waugh, 12/9/1952). It was becoming clear that some sort of program was needed to allow high school students to experience collegiate level academics which still in their secondary careers.

The following year began with the committee continuing to consider Waugh’s proposal (Waugh, 1/12/1953). On February 9, 1953, the University Senate voted to adopt Waugh’s proposal. The program would move forward. In April, Waugh discussed his proposal with Mr. Ebner of Willimantic, who noted that his daughter, at top of the junior class at Windham High School, would be interested in early admittance to the University (Waugh, 4/13/1953). May of 1953 found Waugh seeking scholarship funding for his proposal (Waugh, 5/5/1953); June found him sending off information to area high school principals about the “new scheme” (Waugh, 6/3/1953).

Pivotal to the development of Waugh’s proposal was a November 5, 1953 meeting with executive committee of the Secondary School Principals Association. Waugh, along with other University representatives, met with the committee over their intended protest of the early admittance decision. Waugh noted that the proposal had now changed to “allowing these outstanding students to stay on in the high school taking work under our supervision and getting college credit for the work” (Waugh, 11/5/1953). In the following year, the University Committees on Scholastic Standards and on Curricula and Courses continued to meet and work on Waugh’s proposal. In September, they considered how the admittance of gifted students was handled. Waugh proposal aligned well with this; he noted that because the gifted students would be able to do extra work and take the University’s examinations, they would be able to receive the accelerated learning they wanted (Waugh, 9/16/1954). And, Waugh noted, they would not have “to choose between enriching their program and taking just as long as other students or taking the same program as other students in less time” (Waugh, 9/16/1954). This proposal would allow students to get-ahead on their post-secondary careers which still in high school with an academically challenging and enriching program. The committee unanimously approved of his idea. In December the committee met to discuss the proposal alongside principals from Manchester High School, Norwich Free Academy, and New London High School (Waugh, 12/14/1954). The proposal was moving toward program implementation.

Waugh and the committee continued to plan and prepare for the program during the following months; in January, they met with department heads in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences to discuss the supervision of the program (Waugh, 1/20/1955). In March, he met with 25 area superintendents and principals to discuss the program, all of whom were enthusiastic about the idea (Waugh, 3/18/1955). They continued to refine the program through the rest of the academic year and the summer. At the end of September, Waugh met with High School Principal’s Association about their new “cooperative program for gifted students” (Waugh, 9/30/1955). In November, Waugh discussed the possibility of the Honors English classes at New Britain High School entering the cooperative program (Waugh, 11/30/1955).

And, at the end of the 1955-1956 school year, that class of New Britain High School students had become part of the Cooperative Program for Superior High School Students. Alongside their peers at Bristol High School (now Bristol Central High School and Bristol Eastern High School), Manchester High School, Norwich Free Academy, Rockville High School, and Woodbury High School (now Nonnewaug High School), these students were the first in the nation to take part in a concurrent enrollment program by taking college courses offered in the high school setting by the University of Connecticut.

All references are from the Albert E. Waugh’s Daily Journal, housed in the Albert E. Waugh Papers at the University of Connecticut Library Archives and Special Collections.

Formative Threads in the Tapestry of College Credit in High School: An Early History of the Development of Concurrent Enrollment and a Case Study of the Country’s Oldest Program (2023)

Abstract

While dual and concurrent enrollment (DE/CE) programs are a frequent part of a student’s secondary educational experience today, relatively little is known about how these programs came to be, what factors influenced their development, and what individual and institutional stakeholders were involved. This paper traces how DE/CE programs were created as one of many educational remedies to issues of articulation and duplication between high schools and colleges and the need for acceleration and enrichment for some students during the early and middle twentieth century. At that time, more students than ever were moving through the educational system, education attainment was increasing, and sociopolitical concerns required new ideas for the acceleration and enrichment of students.

Additionally, this article also provides a historical review of the longest running CE program in the United States, the University of Connecticut’s Early College Experience Program. The historical review seeks to reflect and exemplify how the broader sociopolitical influences discussed in the first section of the paper influenced the creation of the first CE program in the country. Through understanding how one program came to be, the current landscape of DE/CE–as well as the evolution and future directions–can be better understood and contextualized.

Rutkauskas, Carissa and Grant, Kathrine (2023) "Formative Threads in the Tapestry of College Credit in High School: An Early History of the Development of Concurrent Enrollment and a Case Study of the Country’s Oldest Program," Concurrent Enrollment Review: Vol. 1, Article 3.

DOI: http://doi.org/10.14305/jn.29945720.2023.1.1.01

Available at: https://surface.syr.edu/cer/vol1/iss1/3